CASE OF THE WEEK – “Diagnostic value of the rim sign on hepatobiliary scintigraphy (case report) “by Dr ShekharShikare, HOD & Consultant, Nuclear Medicine NMC Royal Hospital Sharjah

The most commonly accepted pathophysiologic mechanism for the appearance of the “hot rim” sign is inflammatory changes from the gallbladder spreading to and affecting the surrounding liver. The “hot rim” sign has clinical relevance because it is associated with a high incidence of perforated or gangrenous cholecystitis. The presence of these above-mentioned conditions increases the likelihood of complications and warrants urgent surgical evaluation. We present the findings of on hepatobiliary scintigraphy and adjunct single-photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography-fused imaging in a case of acalculous cholecystitis, which has been confirmed on histopathology (marked degree of acute gangrenous cholecystitis).

A 33-year-old male presented with severe right upper quadrant pain associated with vomiting and fever, which was not settled with pain killers. Clinical assessment led to a suspicion of acute cholecystitis. C-reactive protein was 96 mg/L (0–10).

Ultrasound of the Abdomen

The gall bladder showed increased bladder wall thickening of about 4.6 mm with sludge inside the gallbladder cavity and a streak of fluid around the pericholecystic edema; no gallbladder stones were noted and there were no changes of acalculous acute cholecystitis.

Computed Tomography Scan Of The Abdomen With Contrast

A distended gallbladder showed an enhancing thickened wall, no evidence of calculus, and significant stranding in the pericolic fat planes that extends to involve the adjacent hepatic flexure region. This may represent acalculous cholecystitis.

99mTc Mebrofenin hepatobiliary Scintigraphy

Hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid dynamic images (0–58 min), static images at 60 min and 120 min, and single-photon emission computed tomography /computed tomography-fused images at 60 minute shows prompt and good hepatic extraction of tracer by the liver. Biliary to bowel tracer excretion was normal. The gallbladder was not visualized during the entire study.

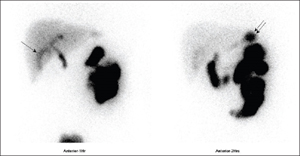

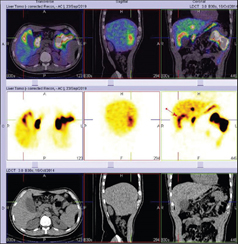

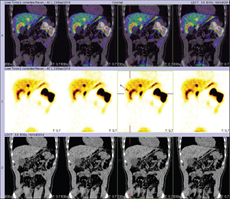

A peripheral rim of abnormally increased tracer uptake was seen surrounding a photopenic gallbladder fossa (rim sign) throughout the study [dynamic images-[Figure 1] (arrow), static images [Figure 2] images-[Figure 1] (arrow), static images [Figure 2] (arrow) and better appreciated in the SPECT/CT fused images ([Figure 3] and [Figure 4] (arrow)).

Figure 1: Dynamic images of hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid scan showing rim sign (arrow).

Figure 2: Static images of hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid scan showing rim sign (single arrow).

Figure 3: Single-photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography images of hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid scan showing rim sign (arrow).

Figure 4: Single-photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography-fused images of hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid scan showing rim sign (arrow).

The Patient underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy and histopathology showed features of marked degree of acute gangrenous cholecystitis.

The “hot rim” sign has been an established marker in hepatobiliary scintigraphy (HBS) since it was first reported in 1984 and the most accepted pathophysiologic mechanism for the appearance of 'hot rim' sign is inflammatory changes from the gallbladder spreading to and affecting the surrounding liver. It is typically seen as a secondary, albeit more specific finding of cholecystitis. It is also a marker of disease severity, as it has an association with more severe forms of cholecystitis, such as perforated and gangrenous cholecystitis.

Typically, acute cholecystitis on HBS is seen as non-visualization of the gallbladder after tracer uptake seen within the biliary tree. The 'hot rim sign' is independent of biliary tracer excretion and instead depends upon the inflammatory reaction of the hepatic parenchyma adjacent to the gallbladder fossa and subsequently resulting hyperemia

The above-mentioned pathophysiologic mechanism of the “hot rim” sign proved useful in diagnosing our patient, as one of our differential considerations before additional imaging was acalculous cholecystitis. The “hot rim” sign lacks association with cases of acalculous cholecystitis, likely secondary to its pathophysiologic cause. Acalculous cholecystitis is typically due to gallbladder immobility in a critically ill patient, with subsequent ischemic insult secondary to the underlying toxic exposure of bile.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic performance of imaging in acute cholecystitis is as follows: sensitivity of hepatobiliary scintigraphy

(96%; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 94%–97%) was significantly higher than the sensitivity of ultrasonography (US) (81%; 95% CI: 75%–87%) and magnetic resonance (MR) imaging (85%; 95% CI: 66%–95%). There were no significant differences in specificity among hepatobiliary scintigraphy (90%; 95% CI: 86%–93%), US (83%; 95% CI: 74%–89%), and MR imaging (81%; 95% CI: 69%–90%). Only one study about the evaluation of CT showed that sensitivity was 94% (95% CI; 73%–99%) at a specificity of 59% (95% CI: 42%–74%). The hepatobiliary scintigraphy has the highest diagnostic accuracy of all imaging modalities in the detection of acute cholecystitis, and the diagnostic accuracy of US has a substantial margin of error, comparable to that of MR imaging, whereas CT is still under evaluated.

Ref – Dr Shekhar V. Shikare. Diagnostic value of the rim sign on hepatobiliary scintigraphy. World J. Nucl Med 2020:19:180-3